Last weekend, on opening day, I had the pleasure of watching my grandson catch two trout with only a small amount of help from me. He will soon be fishing independently. I also enjoyed having the lakes to myself on Sunday afternoon. I had slouched on the wooden bench waiting for the fly line to slowly draw tight, interrupting its drift across the breeze. It was easy fishing, I knew where to fish and how to present the nymph. Arthur Cove documented the method in his book ‘My Way with Trout’ nearly forty years ago.

I knew how to fish at Little Bognor. The weather pattern had changed. The chilly north east wind and bright skies had been replaced by a dull overcast, a warm southerly breeze and showers. Perfect fishing conditions. I wanted to visit the lakes to check on the old Spanish chestnut tree, for a change of scenery and to catch an overwintered brownie.

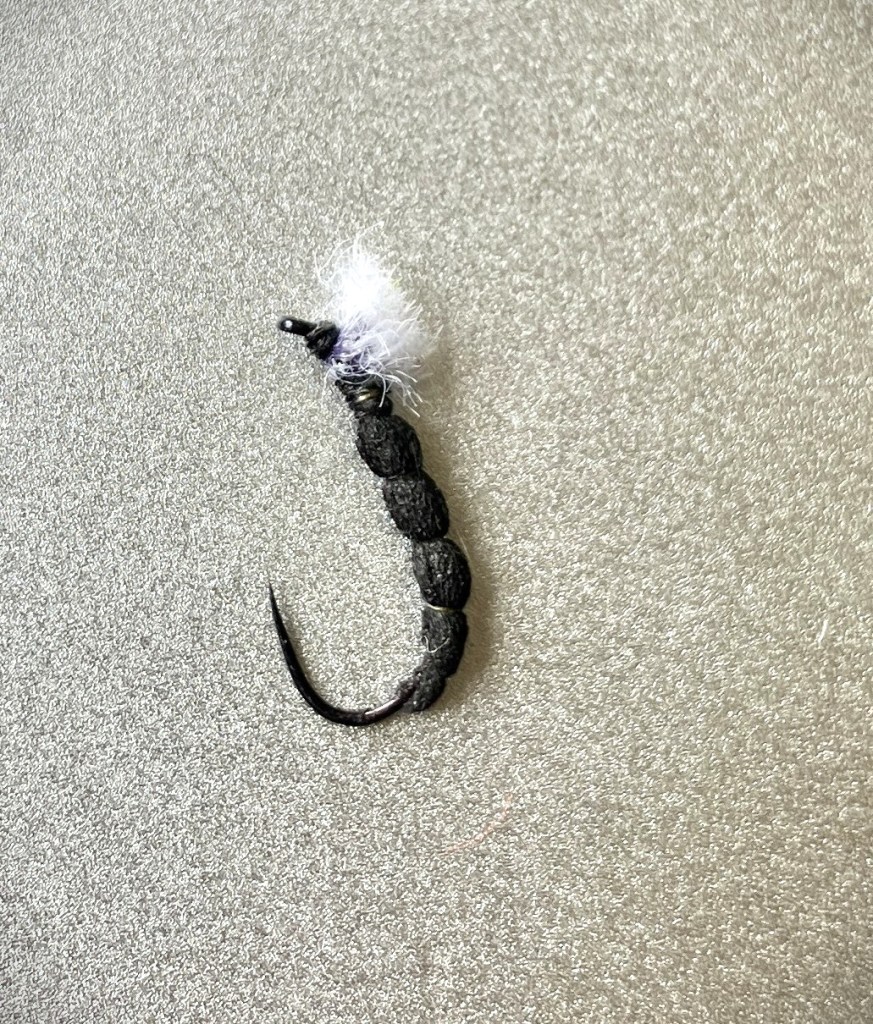

I knew where to fish, the fly pattern to use and how it should be fished. Watching the leader for subtle movements, a slow sinking black buzzer and a very stealthy approach had never let me down. Most anglers keep away from the overhanging trees because the casting is tricky. The line shy trout hide under the overhanging branches, away from the disturbance.

I was surprised to see that the estate forestry team had thinned out the magnificent beech and chestnut wood on the slope to the west of the lakes. It was a professional job that let in light but it had changed the intimate, warm atmosphere around the upper lake. The lower lake had not changed, a buzzard mewed at me while soaring over the tree tops.

The churned up leaf mould on the now open path gave off very earthy smells, it will be a few years before the wood turns green again. The bluebells and primroses will benefit from the sunlight. I was relieved to see that my favourite tree had escaped the chainsaw.

Rex Vicat Cole sketched the dead Spanish Chestnut tree and included the sketch in his book, British Trees, first published in 1907. The tree had been dead for a considerable time when he sketched it and must therefore have first sprouted leaves just after the English civil war in the mid 17th century. It’s roots are firmly embedded in a stone wall and it is protected from gales by the steep sided valley. I’m not a tree hugger but I don’t like thoughtless chainsaw vandalism.

I crouched down, away from the water, to flick a buzzer at passing trout. The heavy tippet was visible in the clear water and after an hour I changed it and rubbed off the shine with damp moss. I caught three trout, one of which was fin perfect and may have been a wild fish. I eventually lost the buzzer attempting an impossible cast through a vertical slot in the overhanging branches.

The number and size of the fish was unimportant, Sir Edward Elgar’s magic trees had been preserved by sensitive forestry management and all was well.

. . . – – – . . .